Clarity Law

A court "mention" is a term that is used every single day in the courts in Queensland but what does it actually mean?

What does a “mention” mean?

A the meaning of a mention is actually quite simple, it is where the magistrate or judge will “mention” a matter in the court. Its purpose is really an opportunity for the judge to find out what’s happening so they can keep the matter progressing through the court system and for any of the parties to raise any issues.

A mention is different to a hearing or a sentence date as it is not always expected that anything of substance would happen at a mention.

First mention

There will always be a first mention of a matter after someone has been arrested. They may be given bail to a first mention date or given a notice to appear in court for a first mention date.

At the first mention date generally the court would be looking for a person to either adjourn the matter to another mention date or plea guilty to a matter or plead not guilty and have the matter set down for a trial.

As it is just a mention if something more complex like a bail application is to occur the court may decide to adjourn that to another date as generally mention won’t do applications or sentences that will take longer than 10-15 minutes.

The courts will almost always grant an adjournment on the first mention court date especially if it is to get legal advice.

At a first mention the police prosecutor should provide the defendant with a copy of their QP9 if they haven’t already. The QP9 is a summary of the facts the police say establish that the defendant is guilty of the offence

You can learn more about QP9’s by reading our article on what is a QP9?

Further court mentions

Complex matters often have a number of mentions throughout the course of the matter. Negotiations with a prosecutor can take time and so a few mentions in court may be required while the negotiations continue.

In our experience if a person has not obtained legal representation then each further adjournment request at a mention will be harder and after 2-3 mentions the court might require someone to enter a plea of guilty or not guilty.

How do I get more information or engage you to act for me?

If you want to engage us or just need further information or advice then you can either;

-

Use our contact form and we will contact you by email or phone at a time that suits you

-

Call us on 1300 952 255 seven days a week, 7am to 7pm

-

Click here to select a time for us to have a free 15 minute telephone conference with you

-

Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

-

Send us a message on Facebook Messenger

-

Click the help button at the bottom right and leave us a message

We are a no pressure law firm, we are happy to provide free initial information to assist you. If you want to engage us then great, we will give you a fixed price for our services so you will know with certainty what we will cost. All the money goes into a trust account monitored by the Queensland Law Society and cannot be taken out without your permission.

If you don’t engage us that fine too, at least you will have more information on the charge and its consequences.

Other articles that may be of interest

A question many clients ask, rightfully so, is will my criminal case be on the news or published on social media?

The answer to those questions are maybe.

In Australia there is a principle called the General Rule of Openness, which has been described as being a fundamental principle of our judicial system. The general rule is that all criminal court proceedings are open to the public and can be freely reported on. There are some exceptions to this rule, mainly surrounding Domestic Violence matters and matters relating to Children, such as Childrens Courts or where Children or victims of sexual assault are giving evidence.

Will there be a reporter in my court?

Whether or not there will be a reporter in court when your matter proceeds are in most cases impossible to tell. Unless you or your legal representative notices a reporter or journalist in the court, the chances are the first time you will know about it is when you see or are made aware of an article written about you.

What is the likelihood of this occurring?

While it is possible that there may be a member of the press in the gallery, the chances of that occurring in most courts is relatively remote. Courts like Court 35 in the Brisbane Magistrates Court which deals exclusively with traffic and drink driving matters, could reasonably expect a lower chance of media being present, than say the Supreme Court where a high-profile trial is going on.

The chances of media being present and whether they will report on a matter will depend on things such as the profile of the defendant and the offences which they have been accused of. Drink or Drug driving doesn’t typically draw the interest of the media unless there is an unusual characteristic about the offender, such as if they are a celebrity, athlete or even a person who is expected to uphold a greater sense of responsibility – like a Doctor, Principal or Lawyer.

Can I do anything to stop it?

Unfortunately, no. It is the general presumption that media are allowed to report freely on court cases, provided they are truthful and accurate. Journalists are required to follow the Court reporting guide for Journalists with respect of their conduct in court, and the Journalist Code of Ethics.

Can I ask the court to close for my matter?

There are exceptionally limited circumstances when the court will close to the public, including media. These include as written above, all children and domestic violence matters, when a witness giving evidence relating to a sexual assault and when a confidential informant is giving evidence.

Conclusion

While it is a naturally distressing time in your life, the thought of an additional punishment in the court of public opinion can add unneeded stress. It is for better or worse an underpinning principle that the administration of justice occurs openly and publicly. The only thing that a defendant can do, is focus on the conduct of their case.

Please note – we do not and cannot give advice on defamation relating to any news organisation publishing information about any case.

Legal Win – Successful Acquittal in Magistrates Court Trial

Written by Jacob Pruden

Recently, I represented a client as solicitor-advocate in a Magistrates Court trial. Solicitor-advocate means I prepared the case and represented the client in court myself, without the aid of a barrister. A Magistrates Court trial means rather than having a jury decide the facts and a judge decide on the law, it was a Magistrate alone deciding both. After the prosecution called its evidence and closed its case, I made a “no case to answer” submission. This submission was successful, and both charges against the client were dismissed.

Some Fundamental Legal Principles

The Queensland system of justice assumes a defendant in a criminal case is “innocent until proven guilty.” Whilst we have seen recent challenges to this fundamental principle in cases of “trial by media”, thankfully, this principle still stands in law.

As the defendant is presumed innocent, the Queensland system of justice requires that the prosecution proves the charges against the accused person. This is called the “burden of proof”.

The way the prosecution proves a charge is by presenting evidence. Not all evidence is admissible, meaning not all evidence will be allowed by the judge or magistrate. The magistrate may disallow evidence if it does not accord with the ‘rules of evidence’, or because it would be unfair to the accused to allow the evidence to be admitted. Objecting to the admission of evidence can be a powerful way for the defence to limit the prosecution case.

The prosecution must prove the charges against the accused “beyond reasonable doubt”. That is, the magistrate or jury must be left with no reasonable doubts about whether the charges against the accused have been proved. If they do have reasonable doubts, then the defendant must be found ‘not guilty’.

For the prosecution to prove a charge against an accused person, they must prove each “element” of each offence. Each offence in Queensland law has one or more legal elements which must be proved to establish proof of the charge. For example, for the prosecution to prove a charge of armed robbery, they must prove:

- The defendant stole something.

- At the time of, or immediately before, or immediately after, stealing it, the defendant used or threatened to use actual violence to any person or property.

- At the time, the defendant was armed with a weapon.

In this example, if the prosecution were able to prove that the defendant stole something from a person, but they could not prove that violence was used or threatened, then they could not prove the charge. Notice, the question is not specifically whether the accused did anything wrong in general, the question is whether he committed the specific offence that he is charged with.

Legal Argument

The reason I have explained the above principles is because I had to rely on all of them to get the charges against my client dismissed. Most criminal trials are decided on the facts, not the law. In this case, however, the law became an important factor in the outcome.

I cannot be too specific about the details of the case for reasons of confidentiality. But in general terms, the case was decided on a fairly complex legal argument involving: the legal meaning of circumstantial evidence, the legal meaning of intent (intent being an ‘element’ of the offences), the admissibility of evidence, the legal meaning of ‘damage’, whether the prosecution could prove its case beyond reasonable doubt, and the legal test required for a “no case to answer” submission to succeed.

Case Strategy

How did I know what points to argue? By having a clear case strategy.

Before the trial started, I knew I was going to make a ‘no case’ submission. My case strategy relied on the prosecution’s mistakes and their weak evidence. I knew roughly what the evidence would be in advance because the prosecution must disclose their evidence before the trial. Everything I did in the trial was aimed at minimising the prosecution evidence by making objections to the admission of evidence and not asking witnesses many questions. The prosecutor did not get a damaging conversation between my client and a witness into evidence. The prosecutor made a mistake. By the close of the prosecution case, the evidence they had was weak enough that I argued they could not prove their case beyond reasonable doubt, and therefore there was no prosecution case for my client to respond to.

After a complex legal argument, the magistrate agreed, and dismissed the charges.

Once you cut out the legal jargon, the main reasons we won were:

- I had a clear strategy.

- I capitalised on the prosecution’s mistakes.

- I never lost sight of the fact the prosecution must prove the charges.

Always remember: the defendant legally is not required to prove anything. He or she is presumed innocent until proven otherwise.

Conclusion

What I have written may come off as hard to understand. That’s an unfortunate by-product of the complexity of our legal system, and why expert legal representation is so important: when your future is on the line, you need experienced and expert legal advocates. You need people in your corner who understand the legal system and use it to your best advantage.

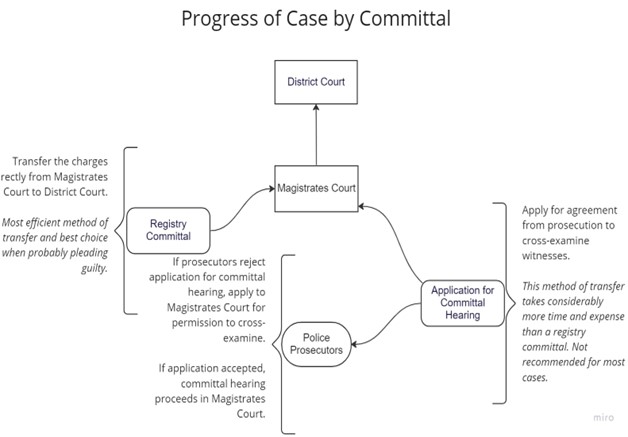

Most charges in Queensland begin and end in the Magistrate Court. The more serious charges, however, must be transferred from the Magistrates Court to the District/Supreme Court.[1] This is called ‘committing’ them. The transfer process is according to this chart:

Steps Before Committal

Full Brief of Evidence and Case Analysis

The “full brief of evidence”, is an assembly of (most of)[2] the evidence the police possess that they say proves the charges against a defendant. This evidence must be given to the defendant (or Clarity Law) before his or her case is committed to the District/Supreme Court. We then assess the evidence to determine whether the evidence is sufficient to prove the charges.

Case Example

We had a client who was charged with grievous bodily harm,[3] which is a charge that must be heard in the District Court. However, after we assessed the medical evidence, it became apparent that evidence supported a less serious charge of assault occasioning bodily harm.[4] We wrote to the prosecution pointing out this discrepancy, and argued the charge should be downgraded. The prosecution accepted this argument, and the charge was downgraded. This meant that the case stayed in the Magistrates Court, which was less costly to the client (in terms of legal fees) and exposed the client to lower maximum penalties.

Confirm Instructions

After we have analysed the evidence (with instructions from the client in mind), we comprehensively explain the evidence, what charges we think can or cannot be proved, and then explain the options and seek directions on what to do next.

The Committal Process

There are two ways[5] of transferring a case from the Magistrates Court to the District/Supreme Court, as explained below.

Registry Committal

This process is a matter of completing the correct paperwork, identifying which charges can be committed, and forwarding the paperwork to the prosecution, who then sign their side of it and file it with the Magistrates Court. This option is the fastest, the least costly, and is best suited to those who are going to plead guilty.

Application for Committal Hearing

This process is much more complicated than the registry committal.

It requires the preparation of a written application, given to the prosecution, which states:

-

Which witnesses we propose are called and cross-examined,

-

The issues we aim to explore with the witness,

-

the reasons we want the witness called.

The questions we ask the witness will be limited to the issues identified in our written application.

The prosecution can accept or reject our application. If it is accepted, then the case is listed for a committal hearing in the Magistrates Court. If the application is rejected, we can still apply directly to the Court and make arguments why the application should be accepted. If the Court rejects it, the application fails. If the Court accepts it, then the case is listed for a committal hearing. It is very important we do not press for a committal hearing to only fish for information; if a complainant or other witnesses are made to come to court to give evidence before the trial, this can greatly reduce the benefit of a guilty plea if a defendant pleads guilty later.

The main purpose of a committal hearing is to test whether the evidence is sufficient to put a defendant on trial for any indictable offence. It is also for a defendant to properly understand a case against him and clarify important ambiguities in the full brief of evidence.

Case Example

A defendant is accused of murder. The circumstances are she was having an argument with a friend near the side of the road. She threatened to stab him and he then stepped out onto the road and was hit and killed by a car. The prosecution argued that, if not for her threatening actions, the man would not have died, and it was therefore murder. The defence argued the prosecution had no evidence to prove it was the defendant who caused the deceased man to step out onto the road, and even if she did, that is not sufficient to establish a charge of murder. The magistrate threw out the murder charge on the basis there was not sufficient evidence that a jury could convict the accused.

An application for a committal hearing is best suited to those cases where a defendant is quite sure he will plead not guilty in the higher court, or the prosecution case is so weak it is worth challenging in the Magistrates Court.

After Committal

Once the case is committed to the higher court, the case and evidence are transferred from the police prosecutors to the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP for short). The ODPP then decide whether to indict (that is charge) the defendant on the same charges, or different charges. Sometimes this will consist of additional charges (if there is something police may have missed, based on the evidence), or fewer charges. It must be assessed on a case-by-case basis whether the charges are likely to change or remain the same.

The ODPP is expected to present the charges to the District or Supreme Court within six months of the committal.

Conclusion

Deciding how to proceed at the committal stage is an important step in every criminal case. This is a decision that should be made with the assistance of expert legal advice. We at Clarity Law have the experience and expertise required to help you navigate through this tricky process.

[1] Justices Act 1886(QLD),sections 108 to 134.

[2] There is some evidence the prosecution is not obliged to give, but will give if requested.

[3] With a maximum penalty of 14 years.

[4] With a maximum penalty of 7 years.

[5] There are technically three ways. The third way is a “full hand up” committal, but this procedure is rarely used.

Parole is when a defendant is supervised in the community by a corrections officer. A person will be placed on parole after he or she has been sentenced to imprisonment. The parole date can be on any day of a prison sentence, including the first day.

Types of Parole

There are two types of parole: court ordered parole and board ordered parole. These are otherwise called a ‘parole release date’ or ‘parole eligibility date’. Court ordered parole is when the Court orders the date a defendant is released on parole. Board ordered parole is when the Court sets a date that the defendant is eligible to apply for parole. When the date set by the Court comes, that is when a prisoner can apply to the parole board for parole. It is then the parole board’s decision whether to release the prisoner on parole. The parole board has 120 days to make a decision about a prisoner’s parole, or if the parole board has deferred its decision, 150 days.

In practical terms, once a person is released on parole the only difference between the two types is the parole board can suspend, vary or cancel a person’s parole if they discover they were given wrong information as part of the prisoner’s parole application.

When Does an Eligibility Date Apply?

If a defendant is sentenced for a serious violent offence[1] or a sexual offence.

a. A serious violent offence is when a person is sentenced for a violent offence for a period of 10 or more years.

b. A sexual offence is any sexual offence.

If a defendant is sentenced for a prison term longer than three years.

If the defendant was on parole, his parole was cancelled by the parole board, and the Court sentences him to a new term of imprisonment.

The defendant was on parole and he is sentenced to a term of imprisonment for an offence committed while on parole.

When does a Parole Release Date Apply?

If a parole eligibility date does not apply, then a parole release date will apply.

What is Parole?

Parole is when a person is serving a prison sentence, but doing so in the community. Under the mandatory conditions of parole include, a defendant must:

- report as directed to their supervising Office;

- carry out the lawful instructions issued by their supervising officer;

- give a test sample if required;

- notify of any change of address or employment details; and

- not to commit an offence.

The idea of parole is to supervise a defendant in the community while he serves the rest of his sentence. It also gives a defendant a greater opportunity to rehabilitate than he would have in prison.

If a person breaches any condition of his or her parole, the parole board has the power to cancel or suspend the parole, even if it was court-ordered parole.

What Happens if Parole Conditions are Breached?

According to the Corrective Services Act 2006, section 205, the parole board may, by written order—

- amend, suspend or cancel a parole order if the board reasonably believes the prisoner subject to the parole order—

has failed to comply with the parole order; or

poses a serious risk of harm to someone else; or

poses an unacceptable risk of committing an offence; or

is preparing to leave Queensland, other than under a written order granting the prisoner leave to travel interstate or overseas; or

-

amend, suspend or cancel a parole order, other than a court ordered parole order, if the board receives information that, had it been received before the parole order was made, would have resulted in the board making a different parole order or not making a parole order; or

-

amend or suspend a parole order if the prisoner subject to the parole order is charged with committing an offence; or

-

suspend or cancel a parole order if the board reasonably believes the prisoner subject to the parole order poses a risk of carrying out a terrorist act.

What Does the Parole Board Consider?

When deciding whether to release a person on parole, the parole board will consider multiple factors which include:

- the prisoner’s criminal history and pattern of offending;

- whether there are any circumstances likely to increase the risk the prisoner presents to the community;

- whether the prisoner has been convicted of a serious sexual offence or serious violent offence;

- any comments made by the Judge during the sentence hearing;

- any medical, psychological or psychiatric risk assessment reports relating to the prisoner – tendered at sentence or obtained while the prisoner has been in jail;

- the prisoner’s behaviour in prison;

- whether the prisoner has access to supports or services in the community;

- whether they have suitable accommodation upon release; and

- the prisoner’s progress and compliance in undertaking any recommended rehabilitation programs and interventions while in prison.

Conclusion

As can be seen, the law around parole and parole conditions is strict. While we at Clarity Law do everything possible to avoid our clients going to jail, sometimes it is inevitable. If it must happen, we have the knowledge and expertise to explain a parole order in detail, to ensure you have the best chance of completing your order.

[1] If a person is sentenced for a serious violent offence, he must serve the lesser of 80% of his term of imprisonment, or 15 years, before eligible for parole.

Help! A Family Member Has Been Arrested: What Can I Do?

Written by Steven Brough

It can be quite the shock when a family member or partner is suddenly arrested. There will be stress, confusion and a desire to try and help.

This article is for family members or partners of some one who has been arrested.

The arrest process

The police are not required to give someone notice that they intend to come and arrest them. The police might very well turn up later in the day or on the weekend.

In general the police will make a formal arrest, detain the accused and take them for questioning.

At this stage you should:

-

If present then get details of the officers and where they are being taken

-

Note down any relevant things the police may have said

-

Don’t contact any witnesses

-

Don’t try and explain anything about the alleged offence to the police

It is absolutely critical for ever Queenslander who is taken in for question to remember that apart from the questions below no one should give an statement or information to a police officer without legal advice. Helping the police at this point will at the best not affect the case against someone but at worse will see them convicted based on what they say.

It’s worth repeating DO NOT TALK TO POLICE without legal advice.

We have a couple of articles that goes more in depth on this issue.

The only questions you need to answer are:

- your name and address

- date and place of your birth

Where have they been taken?

The accused will be taken to a local watchhouse. The locations of local watch houses overlap and some close on the weekends so the accused may be taken to a larger watch house further away.

This is why it’s a good idea to ask police which watch house they are taking the family member to.

Can I attend the police interview?

The accused has the right to request a support person and have that support person attend a police interview.

The accused also has the right to speak to a lawyer.

You would have seen earlier however we strongly advice no one to talk to police at all and certainly not until they have legal advice. If a family member asks you to attend a formal interview you should;

-

Attend the interview

-

Ask the police to explain the right to silence to the family member

-

Tell the family member they should not answer any police questions until they speak to a lawyer

-

Not answer questions for the family member in the police interview or give information or your opinion on any allegations the police pout to the family member during a police interview.

Again It’s worth repeating DO NOT TALK TO POLICE without legal advice.

Can I talk to them in custody?

The police don’t need to allow the family member to call you however most the watch house staff are generally pretty good at allowing at least one call to family.

How long can the police hold them?

The police can detain someone for 8 hours and during that time question them for up to 4 hours. The police would then need to make a decision as to whether they will grant police bail. See below about bail.

What can I do to help?

The most important thing anyone can do to help a husband, wife, son, brother or another family member facing questioning by police or who has already been arrested is get them a lawyer and do it urgently.

Time matters in these situations. A lawyer can quickly contact the police officers and ask to speak to the family member and can give them legal advice.

Remember the family member can say things to police, even innocently, that will mean they will be found guilty of an offence. We see it every single week. Someone has been arrested, they think they can talk the police and prove they are innocent, they say something that leads to;

-

Admitting all or part of the legal requirements for an offence conviction

-

Preventing their lawyer from being able to negotiate with the prosecutor to withdraw or reduce a charge

-

Preventing a valid defence being used at trial

Everyday people in Queensland talk to police and as a result of talking to police are found guilty of an offence. Many, if they had just invoked their right to silence, would never have had charged bought against them or if they had they would have been found not guilty.

Again It’s worth repeating for the third time DO NOT TALK TO POLICE without legal advice.

Will they get bail?

Bail under Queensland law in its simplest form is a promise by the defendant to go to the court on another date. If bail is granted they are released from custody and don’t have to remain in custody while there matter goes through the court.

If the family member is arrested then the police must make a decision as to whether they will be granted bail or not. If they are granted bail they can leave the watch house. If they are not granted bail then they must be bought before Magistrate as soon as possible. This would generally be the next morning (or if it’s the weekend then by Monday morning).

If a Magistrate is to make a decision on whether to grant bail the presumption is they should get bail (except for certain serious offences). However the Magistrate will refuse bail if there is an unacceptable risk that the defendant, if released on bail—

- would fail to appear and surrender into custody; or

- would, while released on bail—

o commit an offence; or

o endanger the safety or welfare of a person who is claimed to be a victim of the offence with which the defendant is charged or anyone else’s safety or welfare; or

o interfere with witnesses or otherwise obstruct the course of justice, whether for the defendant or anyone else; or

o that the defendant should remain in custody for the defendant’s own protection.

In deciding whether there is an unacceptable risk as stated above, the Magistrate must have regard to matters including:

-

the nature and seriousness of the offence;

-

the character, antecedents, associations, home environment, employment and background of the defendant;

-

the history of any previous grants of bail to the defendant;

-

the strength of the evidence against the defendant;

-

if the defendant is an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person—any submissions made by a representative of the community justice group in the defendant’s community;

-

if the defendant is charged with a domestic violence offenceor an offence against the Domestic and Family Violence Protection Act 2012, section 177 (2)— the risk of further domestic violence or associated domestic violence being committed by the defendant. Bail for Domestic Violence offences are what is known as show cause bail applications.

You can learn more about bail by clicking on our bail article.

If the family member doesn’t have a private lawyer then the duty lawyer will visit them in the watch house. However the duty lawyer is very busy so will only have a few minutes to talk.

If they don’t get bail what happens?

If bail is not granted then the family member will remain in custody until the charges are finalised or if bail is granted by a judge of the Supreme Court.

They will be moved as soon as possible to a prison or remand centre. This can take several days. You can find out when they arrive at the prison by:

- using the search for prisoners form

- emailing This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Once they are in prison you can arrange to visit and the family member can also call you.

The first court appearance

After the Court refuses bail they will set a date for the next court appearance. This could be in several weeks time.

You will be able to attend the court on that date (unless the Magistrate closes the court ). The family member will likely appear by video link not in person.

I’m really stressed

Thats really understandable. We also suggest family members see their doctor to get help with coping with a family member in prison.

Don’t try and take all the problems on your own shoulders.

How can I help my family member cope with the charges?

What you need to understand for a prisoner life slows down. They have all day to think about their situation and this can cause them quite a lot of stress.

You will need to remember they will be stressed when they ring you and other family members. Try and keep their hopes up but don’t give them false hope.

Their lawyer will be able to answer any legal questions so try and just concentrate on other things.

What difference will a lawyer make?

It will make all the difference. Having lawyer will best protect their rights, increase their chances of bail and either defend them at trial or reduce their sentence if they plead guilty.

A summary of what a lawyer can do for your family member is:

-

Protect their rights

-

Look for possible defences

-

Get bail

-

Explain the process to the family

-

Update the family on what is occurring

-

Get an enduring power of attorney signed so the family can take pay the family members bills like rent, phone bills and keep their “outside life going”

-

Reduce the sentence

Why should I engage Clarity Law?

Quite frankly we care about getting the right outcome for our clients and helping them through one of the most difficult times in their lives.

In the face of a criminal law charge, selecting the right legal representation is paramount, and Clarity Law offers a unique blend of proficiency and empathy that sets us apart. Our firm is dedicated to providing clarity in the often complex world of criminal law. We believe that every client deserves a clear understanding of their rights and the legal process they're navigating.

Our experienced team of lawyers approaches each case with a commitment to open communication, ensuring you're informed every step of the way. With a proven track record of securing favourable outcomes, we have the expertise to navigate even the most intricate legal challenges.

At Clarity Law, we strive not only to be your staunch advocates but also to provide a supportive, understanding environment during this trying time. Choosing Clarity Law means choosing a team that will tirelessly work to protect your rights and pursue the best possible outcome for your case.

You can read more about our founder, Steven Brough’s, journey to starting Clarity Law by clicking here.

How do I get more information or engage you to act for me?

If you want to engage us or just need further information or advice then you can either;

-

Use our contact form and we will contact you by email or phone at a time that suits you

-

Call us on 1300 952 255 seven days a week, 7am to 7pm

-

Click here to select a time for us to have a free 15 minute telephone conference with you

-

Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

-

Send us a message on Facebook Messenger

-

Click the help button at the bottom right and leave us a message

We are a no pressure law firm, we are happy to provide free initial information to assist you. If you want to engage us then great, we will give you a fixed price for our services so you will know with certainty what we will cost. All the money goes into a trust account monitored by the Queensland Law Society and cannot be taken out without your permission.

If you don’t engage us that fine too, at least you will have more information on the charge and its consequences.

Other articles that may be of interest

When imposing a prison sentence, a Queensland Court has two primary discretions. The first is to decide the length of the sentence, and the second is to set the release or eligibility date.

The basic structure of prison sentences

A prison sentence might be “six months imprisonment to be released on parole after having served two months”. This means that the prison sentence is six months, and the person is released from custody after two months. The remaining four months will be served on parole. Alternatively, the Court may order that the person serves four years to be eligible for parole after two years.

The two parts, then, are the length of the sentence, and then a parole release or parole eligibility date some time before the end of the sentence.

Setting length of the sentence

Sentencing in Queensland is a complex procedure in which the Court must consider many things, including:

-

The sentencing principles in the Penalties and Sentences Act;

-

Relevant case law (previously decided cases);

-

the maximum penalty of the offence;

-

the penalty submissions made by the prosecution;

-

the penalties submissions made by the defence;

-

the personal circumstances of the defendant;

-

the circumstances of the offence;

-

any victim impact statement;

-

the impact the offence had on an individual or the public generally;

-

any time in custody the defendant has already served before the sentence and;

-

the criminal history of the defendant.

As can be seen, there is a lot for the Court to consider.

The Queensland Supreme Court has said that sentencing is not a mathematical exercise. Judges and magistrates have a wide discretion in deciding how to impose a sentence. The primary approach is called an “instinctive synthesis”.

In practice, most judges and magistrates are likely to stay within the “range” of previously decided cases. “Range” means the upper and lower limits of the usual sentences imposed for a given offence. For example, a court is likely to impose a penalty of 18 months or more for drug trafficking. This is because most cases show sentences of 18 months imprisonment or more for that offence.

Setting the Release Date

It is rare for a defendant to serve the whole of the length of his prison sentence in custody. He will usually have the opportunity of parole.

As a general rule, a person who pleads ‘guilty’ to an offence will be released or eligible after serving approximately 1/3 of his or her sentence. A person who pleads ‘not guilty’ and loses the trial, will generally be released or eligible after 1/2 of the sentence.

The longer the sentence, the more difference this makes. The difference between 1/3 or 1/2 of six months is one month. The difference between 1/3 or 1/2 of five years is 10 months.

Release Date or Eligibility Date

When a court is deciding when to release a person on parole, it will impose either a “parole release date”, or a “parole eligibility date”.

A parole release date means the Court chooses the date of the defendant’s release. This can be anywhere from the first day of the sentence to the last day.

If the Court does not impose a release date, it will be an eligibility date. This means the Court will set the date for when the defendant is eligible to apply for parole. The defendant applies to the Parole Board for release. It is the Parole Board who decides his release date, as opposed to the Court. The parole board has up to 120 days after the prisoner’s parole application to decide whether to release the prisoner or not. The Parole Board may defer the decision to gather further information, in which case it has 150 days to decide. So, while the prisoner can apply for parole, it may not be granted for up to 150 days after his application.

What is the Most important factor for sentencing?

In our experience, every case is different, and no one case will necessarily be decided in the same way as another. However, the factors below will always be relevant.

The seriousness of the offence. This refers to how seriously the offence is considered at law. A person convicted of murder is always going to do jail time, regardless of every other factor, because of how serious the offence is. A person convicted of possessing a pipe to smoke drugs, however, is almost never going to be sentenced to jail. This is because the offence is not serious enough to warrant actual imprisonment.

Criminal history is a big factor. A person may commit an offence which is not especially serious, but because of his criminal history, it becomes serious. Breaching a domestic violence order is a common example of this. The breach itself may not be overly serious, but because the person has been sentenced for breaching domestic violence orders many times in the past, the Court may consider it has no other option but to impose actual imprisonment.

As outlined earlier, a court will consider previous cases which are similar to the one before it, and attempt to impose a sentence within those bounds. This is for the purpose of (among others) consistency. It would be unfair for one person to get a wildly different penalty from another person for the same offence.

Conclusion

This article is only an introduction to sentencing. We highly recommend if you are charged with any offence, let alone a serious one, that you engage experienced criminal law experts. Clarity Law can give you the individual advice and support you need to make the right move.

Why should I engage Clarity Law?

Quite frankly we care about getting the right outcome for our clients and helping them through one of the most difficult times in their lives.

In the face of a criminal law charge, selecting the right legal representation is paramount, and Clarity Law offers a unique blend of proficiency and empathy that sets us apart. Our firm is dedicated to providing clarity in the often complex world of criminal law. We believe that every client deserves a clear understanding of their rights and the legal process they're navigating.

Our experienced team of lawyers approaches each case with a commitment to open communication, ensuring you're informed every step of the way. With a proven track record of securing favourable outcomes, we have the expertise to navigate even the most intricate legal challenges.

At Clarity Law, we strive not only to be your staunch advocates but also to provide a supportive, understanding environment during this trying time. Choosing Clarity Law means choosing a team that will tirelessly work to protect your rights and pursue the best possible outcome for your case.

You can read more about our founder, Steven Brough’s, journey to starting Clarity Law by clicking here.

How do I get more information or engage you to act for me?

If you want to engage us or just need further information or advice then you can either;

-

Use our contact form and we will contact you by email or phone at a time that suits you

-

Call us on 1300 952 255 seven days a week, 7am to 7pm

-

Click here to select a time for us to have a free 15 minute telephone conference with you

-

Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

-

Send us a message on Facebook Messenger

-

Click the help button at the bottom right and leave us a message

We are a no pressure law firm, we are happy to provide free initial information to assist you. If you want to engage us then great, we will give you a fixed price for our services so you will know with certainty what we will cost. All the money goes into a trust account monitored by the Queensland Law Society and cannot be taken out without your permission.

If you don’t engage us that fine too, at least you will have more information on the charge and its consequences.

Other articles that may be of interest