Clarity Law

Jacob Pruden

Jacob is a former barrister and now criminal defence lawyer with over 8 years experience appearing in courts throughout South East Queensland representing clients charged with criminal offences.

When are you required to give police your name and address?

Queensland Police can, unsurprisingly, exercise a wide variety of quite coercive powers. We all know police can arrest and detain people, seize evidence related to crime, and compel people to provide information. These powers are all necessary so police can carry out their important function of investigating unlawful conduct and charging suspects.

What people may not know is police power is not unlimited, and there are important safeguards in place to ensure police know the limits of their powers and do not exceed them.

A police officer may require you to state your correct name and address in prescribed circumstances.

The police officer may also require you to give evidence of the correctness of the stated name and address if it would be reasonable to expect you to be in possession of evidence of the correctness of your name or address or to otherwise be able to give that evidence.

So when can police ask for my name and address?

The prescribed circumstances in which police can require you to state your name and address in Queensland are as follows—

-

a police officer finds you committing an offence;

-

a police officer reasonably suspects you have committed an offence;

-

a police officer is about to take—

o your fingerprints; or

o a DNA sample from you;

-

a police officer is attempting to enforce a warrant, forensic procedure order or serve on you—

o a forensic procedure order; or

o a summons; or

o another court document;

-

a police officer reasonably suspects you have been or are about to be involved in domestic violence or associated domestic violence;

-

a police officer reasonably suspects you may be able to help in the investigation of—

o a domestic violence or associated domestic violence; or

o a relevant vehicle incident;

-

a police officer reasonably suspects you may be able to help in the investigation of an alleged indictable offence because you were near the place where the alleged offence happened before, when, or soon after it happened;

-

you are in control of a vehicle that is stationary on a road or has been stopped;

-

a police officer is about to give, is giving, or has given you a police banning notice;

-

a police officer is about to give, is giving, or has given you—

o a public safety order;

o a restricted premises order;

o a fortification removal order;

-

a police officer reasonably suspects you have consorted, are consorting, or likely to consort with 1 or more recognised offenders.

If a police officer is speaking to you and you do not know or understand why, you are entitled to ask the officer the reason for speaking to you and if the officer is requesting your name and address, you may ask the reason for that, too. But, if you are given an answer other than “because I said so” it is best to comply, as you can be charged with an offence of contravening a direction or requirement of a police officer. It is a fine only offence.

You are entitled to ask a police officer to provide his or her name, rank and identification number. You may ask a police officer to record an interaction the officer is having with you, or you may wish to record the interaction yourself.

If police ask you questions which you believe are in connection with an offence in which you are a suspect, you have a right to refuse to answer those questions and seek legal advice.

Conclusion

As can be seen, there are a wide variety of circumstances where police may ask you your name and address, but it is important police explain why such details are required. There all sorts of reasons why police interact with the public, and the taking of your details will generally go no further than taking a note in a notebook. If you are subsequently charged, it is strongly recommended you contact a lawyer, and you should certainly contact a lawyer before any proposed interview.

How long do criminal convictions stay on my record?

When a court finds someone guilty of an offence that court has a discretion whether to record a conviction or not. In that case, the Court will consider, according to the provisions of section 12 of the Penalties and Sentences Act, whether or not to do so. If the Court does not record the conviction, then it will not appear on a standard police check.

This short article, however, is more concerned with how long a conviction will stay on your record if a conviction is recorded or in other words when is a conviction “spent” in Queensland?

To find that out, we look at the Criminal Law (Rehabilitation of Offenders) Act 1986.

The rehabilitation period

The act refers to a ‘rehabilitation period’, which means a person need not disclose, or agencies (such as police) must not disclose, a previously recorded conviction after a certain period, as explained below.

How long will a criminal conviction in the Magistrates Court last?

The rehabilitation period for a summary offence, that is, an offence dealt with in the Magistrates Court, a conviction will not remain visible on your record 5 years from the date of the conviction. This is so long as no other offences have been committed in the meantime.

How long will a criminal conviction in the District or Supreme Court last?

The rehabilitation period for an indictable offence, that is, an offence dealt with in the District or Supreme Court, a conviction will not remain visible on your record 10 years from the date of the conviction so long as no other offences have been committed in the meantime.

Will the fact I was sentenced to prison affect the time the conviction remains on my record?

Possibly, a conviction will remain on your record forever if you were sentenced to a term of imprisonment for the offence, with time actually served. Otherwise, where you have been sentenced to a term of imprisonment of 30 months or less.

What exceptions to the normal rules exist?

There are multiple other exceptions however with some listed below:

-

A conviction will still appear on your criminal history if relevant for a criminal or civil court proceeding. For example if you go to court for a new criminal charge the court can get access to all your previous convictions.

-

If restitution was ordered then if it has not been paid by the time the rehabilitation period ends the conviction remains until the rehabilitation has been paid in full.

-

It is likely that it would still be required for you to disclose an excluded conviction if you were to apply for Australian citizenship or a blue card.

-

An excluded conviction may still be disclosed if you are seeking admission to a profession, occupation, or calling prescribed by regulation. For example, a lawyer, police officer or corrective services officer.

-

All previous convictions would remain in law enforcement databases.

-

For commonwealth offences where the sentenced occurred in Queensland the rehabilitation period is 10 years no matter which court heard the charge.

In conclusion, the law allows some scope for prior convictions to be hidden from your record.

I had a conviction 15 years ago and I don’t have to disclose it but I’m applying to be a teacher and the form says I must disclosure all convictions

The law specifies where a person must still disclosure a conviction no matter what. They can include:

-

a person applying to be a teacher

-

a person applying to be a lawyer

-

a person applying to be a police officer

-

a person applying for a blue card

You can click here to see the full list.

Can I apply to expunge my conviction early?

No, there is no way to speed up the process and get the conviction removed before the rehabilitation period has ended.

The only rare exception is for people with historical convictions for homosexual offences prior to 1991.

So after the rehabilitation period has ended can I say I was never convicted of an offence?

You can generally say you have no convictions if you meet all the following (see also the exceptions above):

-

you weren't sentenced to imprisonment as part of your sentence or you were sentenced to prison for less than 30 months (regardless of whether you actually had to go to prison)

-

the rehabilitation period (5 years for Magistrates Court convictions, and 10 years for District and Supreme Court convictions or commonwealth convictions) has expired

-

you haven't broken the law since your conviction

-

you have paid any restitution ordered

Remember if no conviction was recorded at the time of the offence then the offence does not appear on your criminal record ever. This article is just about where a conviction was recorded.

Going armed so as to cause fear

This article is all about the Queensland charge of going armed so as to cause fear charge.

The Law

This offence is contained in section 69 of the Criminal Code. The section states:

“ Any person who goes armed in public without lawful occasion in such a manner as to cause fear to any person is guilty of a misdemeanour, and is liable to imprisonment for 2 years.”

The three key ingredients, then, are that:

-

the defendant was in public,

-

openly armed,

-

in a manner likely to cause fear.

In practical terms, the circumstances are important. A person holding a cricket bat in his yard playing a game with his kids is very different from the same man holding a cricket bat in a neighbour’s driveway, calling the neighbour out for a confrontation.

Lawful occasion

It may be noticed in subsection (1) that the person must go armed in public “without lawful occasion”. A person might readily contemplate a “lawful occasion” to be an armed police officer or security guard. For a private citizen there might be lawful occasions to be armed. It is unlikely for self-protection or self-defence to be such an occasion when there is no clear and present threat to the defendant.

One case that considered this question of “lawful occasion” was one where a man, who was on his own property, shot his rifle into the air to break up a fight. One of the judges in the case commented:

Other lawful reasons or excuses for going, at least temporarily, armed in public on the outskirts of towns in western Queensland can readily be imagined. Using a rifle to shoot a rabid dog or a wild pig that presents a threat to the safety of people in the area would surely not under s. 69(1) be “without lawful occasion” simply because it takes place in public and causes fear. Here it was not dogs or pigs that Mr Bennett was seeking to restrain, but his own sons, who were engaged in a serious attack on another person. Firing a shot harmlessly in the air in order to bring them to their senses was not only a legitimate reason or lawful excuse for his going armed in public (if that is what he did) but a thoroughly effective one. On hearing the shot fired, Lindsay decided to “cut it out”, as he said, and leave his victim go. Both he and George stopped hitting Barry Facer and returned to the house.

Defences to the charge of going armed so as to cause fear

-

The defendant was not the person who committed the offence

-

The defendant was not in public

-

The defendant was not “armed”

-

The defendant did not act in a manner to cause fear

-

The defendant had a lawful occasion to be armed

Penalty

The maximum penalty is up to 2 years imprisonment.

Penalties can vary widely for this offence. In one case, a man was sentenced to a term of actual imprisonment for pointing a handgun at someone and pulling back the top slide. Though he didn’t shoot the weapon, the court found his actions to be so serious to be deserving of imprisonment. In another case, a man was brandishing a knife in a threatening way. He was also sentenced to imprisonment. Fines or penalties less than imprisonment are also available for this offence. Nevertheless, the courts consider this to be a serious charge and we highly recommend you seek legal advice if you are charged with such an offence.

Which court hears the charge of going armed so as to cause fear

The Magistrates Court closet to where the alleged offence occurred will hear the charge.

Can the charge be withdrawn?

Depending on the circumstances it may be possible to negotiate the charge with the prosecutor. This is called case conferencing. For example it might be possible to try and convince the prosecutor that the wounding was excused by law or the medical evidence does not meet the standard for a wounding charge and therefore the charge should be withdrawn.

Will I get a criminal conviction if I plead guilty to the charge?

The answer is possibly. It depends on a number of factors. Only an experienced criminal lawyer can give you advice on the best way to try and avoid a conviction being recorded if you plead guilty to this charge. Note however if imprisonment is part of the penalty then a conviction must be recorded.

Learn more about the difference between a conviction and non-conviction

The police want to talk to me about a going armed so as to cause fear charge

Never ever give an interview to police without first getting legal advice. Even if you are innocent, even if you have a defence you could say the wrong thing and virtually guarantee you will be found guilty of the charge.

The police are not on your side, get immediate legal advice.

Learn more about your right to silence.

I’m not guilty of the going armed so as to cause fear

Still don’t talk to the police. A lawyer would require the prosecutor to give them all their evidence and statements. This is known as the full brief of evidence. Once the brief was received then negotiations with the prosecutor to drop the charge can occur.

Learn more about what to do if accused of a crime you didn’t commit.

How do I get more information or engage you to act for me?

If you want to engage us or just need further free information or advice then you can either;

-

Use our contact form and we will contact you by email or phone at a time that suits you

-

Call us on 1300 952 255seven days a week, 7am to 7pm

-

Click hereto select a time for us to have a free 15 minute telephone conference with you

-

Email the firms founder on This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

-

Send us a message onFacebook Messenger

-

Click the help button at the bottom right and leave us a message

We are a no pressure law firm, we are happy to provide free initial information to assist you. If you want to engage us then great, we will give you a fixed price for our services so you will know with certainty what we will cost. All the money goes into a trust account monitored by the Queensland Law Society and cannot be taken out without your permission or until we are legally allowed to.

Introduction to Liquor Law Infringements

Under Queensland law, the serving of alcohol by business establishments is regulated by legislation, with hefty penalties for non-compliance with the laws. This article will touch on these penalty provisions, rather than the laws with respect to applications for liquor licences.

The Relevant Laws

Liquor Regulation 2002

Liquor (Approval of Adult Entertainment Code) Regulation 2002

Wine Industry Regulation 2009

Offences and Penalties

The liquor laws are enforced by specially appointed police and Office of Liquor and Gaming Regulation investigators. The laws apply to those who sell liquor, whether a licenced premises or even online.

Under the Liquor Act 1992, there are more than 100 offences. They are generally dealt with by way of “on the spot” fines, which can be as high as $3,096 or as low as $309. The higher fines are for such infringements as:

- A manager of a licenced premises selling liquor to a minor.

- A manager of a licenced premises failing to prevent a minor from being in a pokies area.

- A manager of a licenced premises allowing liquor to be supplied to a minor.

- A manager of a licenced premises allowing liquor to be consumed by a minor on the premises.

- Selling liquor without a licence.

- Displaying liquor for sale without a licence.

The lower fines are for such infringements as:

- Failure to comply with Commissioner’s direction to repair ID scanner.

- Licensee fail to keep premises clean or in good repair.

- Fail to obtain approval for premises name change.

- Licensee allow sale, supply or consumption of liquor in car park.

More serious infringements can lead to fines of tens of thousands of dollars and other penalties. For example:

- Allow a disorderly patron to consume liquor: Maximum $77,400.

- Licensee engages in practices or promotions that encourage rapid or excessive consumption of liquor: Maximum $15,480.

- Failure to comply with CCTV conditions: Maximum $15,480.

- Allow intoxicated patron to consume liquor (how many times would this occur each weekend?): Maximum $77,400.

- Selling alcohol without a licence: up to $154,800 and 18 months imprisonment.

In case these eye-watering fines were not enough, the laws also give authorities the power to punish breaches of the Act by forcing a business to limit its opening ours, close its premises, or even cancel its liquor licence entirely.

What If You are Fined for A Liquor Licensing Matter?

An individual or business need not accept an on-the-spot fine, especially in circumstances where operators of the venue or staff had no knowledge of the offence. Offences like “allowing a disorderly patron to consume liquor” raises some subjective questions such as: what is disorderly? What if the person consumed liquor out of sight of staff? What if the person was briefly ‘disorderly’ and then settled down? In ambiguous cases like these it may well be worth challenging a massive fine or licence restriction.

A matter can be challenged in the Magistrates Court. Assuming a solicitor is engaged, this will then open the door to negotiations with the Office of Liquor and Gaming Regulation, with an aim of getting rid of the infringements entirely, or at least reducing the fines. Liquor licences are costly enough as it is (thousands of dollars) without business owners or employees being hit with hefty fines for possibly unintentional infractions.

If you find yourself in such a situation, Clarity Law can help. We are experienced in defending traffic, criminal and regulatory matters. We don’t take Legal Aid cases which means your case will get the attention it deserves.

Will a Criminal Charge Affect a Visa Application?

A foreigner who wishes to visit or remain in Australia must be of good character. Character requirements must be met if a person is to continue holding a visa, apply for a visa, or renew a visa. The Australian Department of Home Affairs manages immigration in Australia, and it is the Minister or her delegates who assess the character requirements as they apply to a visa holder or applicant.

What are the Character Requirements?

The main legislative section that refers to character requirements is section 501 of the Migration Act 1958.

The overarching requirement is for a person to pass a character test. To this end, the government applies a character test to those applying for a visa. The government may also apply the character test to cancel a visa that has already been granted.

One of the key indications of bad character is if a person has a substantial criminal record. A substantial criminal record, among other things, includes being sentenced to a single or combined term of imprisonment of 12 months or more (it does not matter how much time you serve in prison, if any, just that the head sentence was 12 months or more)

Other indicators of bad character include, but are not limited to:

- A person has a proven sexual offence involving a child.

- A person has been convicted of a domestic violence offence or has been subject of a domestic violence order.

- Having regard to the person's past and present criminal conduct and the person's past and present general conduct, the Minister considers the person not to be of good character.

- The Minister believes that, in the event the person was allowed to remain in Australia, there is a risk that the person would:

- engage in criminal conduct in Australia; or

- harass, molest, intimidate or stalk another person in Australia; or

- vilify a segment of the Australian community; or

- incite discord in the Australian community or in a segment of that community; or

- represent a danger to the Australian community or to a segment of that community, whether by way of being liable to become involved in activities that are disruptive to, or in violence threatening harm to, that community or segment, or in any other way.

Significance for Criminal Law

There is no specific section of law that states a person’s visa application or visa status will be affected only by a criminal charge. It is possible, however, that the Department of Home Affairs my consider some allegations serious enough to influence a character assessment prior to a conviction.

Once a person is convicted of an offence, however, this can trigger the cancellation of a person’s visa depending on the nature of the offence, and the extent of the penalty.

If a person is in Australia on a visa and they lodge another visa application, and that application is refused on character grounds, then any current visa is also cancelled.

A cancelation or refusal of a visa can be appealed, if the decision was not made by the Minister personally.

Conclusion

The more serious the criminal conduct, the more likely it will affect a person’s visa status. A person is unlikely to have his or her visa cancelled for a speeding offence or a parking infringement. If the person is charged with a serious offence, however, it would be wise to obtain legal advice regarding the possible implications this may have for the person’s visa status.

Legal Win – Successful Acquittal in Magistrates Court Trial

Recently, I represented a client as solicitor-advocate in a Magistrates Court trial. Solicitor-advocate means I prepared the case and represented the client in court myself, without the aid of a barrister. A Magistrates Court trial means rather than having a jury decide the facts and a judge decide on the law, it was a Magistrate alone deciding both. After the prosecution called its evidence and closed its case, I made a “no case to answer” submission. This submission was successful, and both charges against the client were dismissed.

Some Fundamental Legal Principles

The Queensland system of justice assumes a defendant in a criminal case is “innocent until proven guilty.” Whilst we have seen recent challenges to this fundamental principle in cases of “trial by media”, thankfully, this principle still stands in law.

As the defendant is presumed innocent, the Queensland system of justice requires that the prosecution proves the charges against the accused person. This is called the “burden of proof”.

The way the prosecution proves a charge is by presenting evidence. Not all evidence is admissible, meaning not all evidence will be allowed by the judge or magistrate. The magistrate may disallow evidence if it does not accord with the ‘rules of evidence’, or because it would be unfair to the accused to allow the evidence to be admitted. Objecting to the admission of evidence can be a powerful way for the defence to limit the prosecution case.

The prosecution must prove the charges against the accused “beyond reasonable doubt”. That is, the magistrate or jury must be left with no reasonable doubts about whether the charges against the accused have been proved. If they do have reasonable doubts, then the defendant must be found ‘not guilty’.

For the prosecution to prove a charge against an accused person, they must prove each “element” of each offence. Each offence in Queensland law has one or more legal elements which must be proved to establish proof of the charge. For example, for the prosecution to prove a charge of armed robbery, they must prove:

- The defendant stole something.

- At the time of, or immediately before, or immediately after, stealing it, the defendant used or threatened to use actual violence to any person or property.

- At the time, the defendant was armed with a weapon.

In this example, if the prosecution were able to prove that the defendant stole something from a person, but they could not prove that violence was used or threatened, then they could not prove the charge. Notice, the question is not specifically whether the accused did anything wrong in general, the question is whether he committed the specific offence that he is charged with.

Legal Argument

The reason I have explained the above principles is because I had to rely on all of them to get the charges against my client dismissed. Most criminal trials are decided on the facts, not the law. In this case, however, the law became an important factor in the outcome.

I cannot be too specific about the details of the case for reasons of confidentiality. But in general terms, the case was decided on a fairly complex legal argument involving: the legal meaning of circumstantial evidence, the legal meaning of intent (intent being an ‘element’ of the offences), the admissibility of evidence, the legal meaning of ‘damage’, whether the prosecution could prove its case beyond reasonable doubt, and the legal test required for a “no case to answer” submission to succeed.

Case Strategy

How did I know what points to argue? By having a clear case strategy.

Before the trial started, I knew I was going to make a ‘no case’ submission. My case strategy relied on the prosecution’s mistakes and their weak evidence. I knew roughly what the evidence would be in advance because the prosecution must disclose their evidence before the trial. Everything I did in the trial was aimed at minimising the prosecution evidence by making objections to the admission of evidence and not asking witnesses many questions. The prosecutor did not get a damaging conversation between my client and a witness into evidence. The prosecutor made a mistake. By the close of the prosecution case, the evidence they had was weak enough that I argued they could not prove their case beyond reasonable doubt, and therefore there was no prosecution case for my client to respond to.

After a complex legal argument, the magistrate agreed, and dismissed the charges.

Once you cut out the legal jargon, the main reasons we won were:

- I had a clear strategy.

- I capitalised on the prosecution’s mistakes.

- I never lost sight of the fact the prosecution must prove the charges.

Always remember: the defendant legally is not required to prove anything. He or she is presumed innocent until proven otherwise.

Conclusion

What I have written may come off as hard to understand. That’s an unfortunate by-product of the complexity of our legal system, and why expert legal representation is so important: when your future is on the line, you need experienced and expert legal advocates. You need people in your corner who understand the legal system and use it to your best advantage.

Committal Proceedings

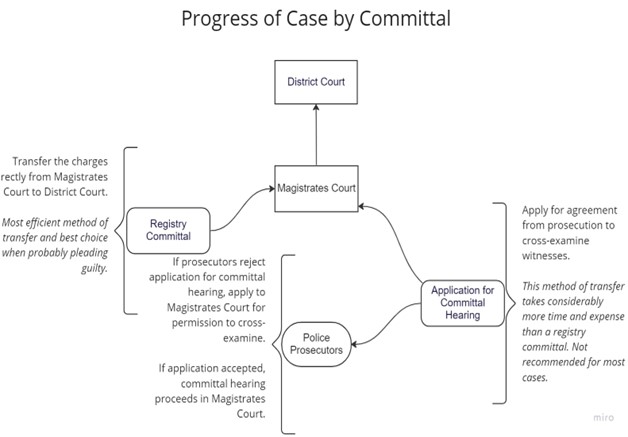

Most charges in Queensland begin and end in the Magistrate Court. The more serious charges, however, must be transferred from the Magistrates Court to the District/Supreme Court.[1] This is called ‘committing’ them. The transfer process is according to this chart:

Steps Before Committal

Full Brief of Evidence and Case Analysis

The “full brief of evidence”, is an assembly of (most of)[2] the evidence the police possess that they say proves the charges against a defendant. This evidence must be given to the defendant (or Clarity Law) before his or her case is committed to the District/Supreme Court. We then assess the evidence to determine whether the evidence is sufficient to prove the charges.

Case Example

We had a client who was charged with grievous bodily harm,[3] which is a charge that must be heard in the District Court. However, after we assessed the medical evidence, it became apparent that evidence supported a less serious charge of assault occasioning bodily harm.[4] We wrote to the prosecution pointing out this discrepancy, and argued the charge should be downgraded. The prosecution accepted this argument, and the charge was downgraded. This meant that the case stayed in the Magistrates Court, which was less costly to the client (in terms of legal fees) and exposed the client to lower maximum penalties.

Confirm Instructions

After we have analysed the evidence (with instructions from the client in mind), we comprehensively explain the evidence, what charges we think can or cannot be proved, and then explain the options and seek directions on what to do next.

The Committal Process

There are two ways[5] of transferring a case from the Magistrates Court to the District/Supreme Court, as explained below.

Registry Committal

This process is a matter of completing the correct paperwork, identifying which charges can be committed, and forwarding the paperwork to the prosecution, who then sign their side of it and file it with the Magistrates Court. This option is the fastest, the least costly, and is best suited to those who are going to plead guilty.

Application for Committal Hearing

This process is much more complicated than the registry committal.

It requires the preparation of a written application, given to the prosecution, which states:

-

Which witnesses we propose are called and cross-examined,

-

The issues we aim to explore with the witness,

-

the reasons we want the witness called.

The questions we ask the witness will be limited to the issues identified in our written application.

The prosecution can accept or reject our application. If it is accepted, then the case is listed for a committal hearing in the Magistrates Court. If the application is rejected, we can still apply directly to the Court and make arguments why the application should be accepted. If the Court rejects it, the application fails. If the Court accepts it, then the case is listed for a committal hearing. It is very important we do not press for a committal hearing to only fish for information; if a complainant or other witnesses are made to come to court to give evidence before the trial, this can greatly reduce the benefit of a guilty plea if a defendant pleads guilty later.

The main purpose of a committal hearing is to test whether the evidence is sufficient to put a defendant on trial for any indictable offence. It is also for a defendant to properly understand a case against him and clarify important ambiguities in the full brief of evidence.

Case Example

A defendant is accused of murder. The circumstances are she was having an argument with a friend near the side of the road. She threatened to stab him and he then stepped out onto the road and was hit and killed by a car. The prosecution argued that, if not for her threatening actions, the man would not have died, and it was therefore murder. The defence argued the prosecution had no evidence to prove it was the defendant who caused the deceased man to step out onto the road, and even if she did, that is not sufficient to establish a charge of murder. The magistrate threw out the murder charge on the basis there was not sufficient evidence that a jury could convict the accused.

An application for a committal hearing is best suited to those cases where a defendant is quite sure he will plead not guilty in the higher court, or the prosecution case is so weak it is worth challenging in the Magistrates Court.

After Committal

Once the case is committed to the higher court, the case and evidence are transferred from the police prosecutors to the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP for short). The ODPP then decide whether to indict (that is charge) the defendant on the same charges, or different charges. Sometimes this will consist of additional charges (if there is something police may have missed, based on the evidence), or fewer charges. It must be assessed on a case-by-case basis whether the charges are likely to change or remain the same.

The ODPP is expected to present the charges to the District or Supreme Court within six months of the committal.

Conclusion

Deciding how to proceed at the committal stage is an important step in every criminal case. This is a decision that should be made with the assistance of expert legal advice. We at Clarity Law have the experience and expertise required to help you navigate through this tricky process.

[1] Justices Act 1886(QLD),sections 108 to 134.

[2] There is some evidence the prosecution is not obliged to give, but will give if requested.

[3] With a maximum penalty of 14 years.

[4] With a maximum penalty of 7 years.

[5] There are technically three ways. The third way is a “full hand up” committal, but this procedure is rarely used.

A guide to parole in Queensland

Parole is when a defendant is supervised in the community by a corrections officer. A person will be placed on parole after he or she has been sentenced to imprisonment. The parole date can be on any day of a prison sentence, including the first day.

Types of Parole

There are two types of parole: court ordered parole and board ordered parole. These are otherwise called a ‘parole release date’ or ‘parole eligibility date’. Court ordered parole is when the Court orders the date a defendant is released on parole. Board ordered parole is when the Court sets a date that the defendant is eligible to apply for parole. When the date set by the Court comes, that is when a prisoner can apply to the parole board for parole. It is then the parole board’s decision whether to release the prisoner on parole. The parole board has 120 days to make a decision about a prisoner’s parole, or if the parole board has deferred its decision, 150 days.

In practical terms, once a person is released on parole the only difference between the two types is the parole board can suspend, vary or cancel a person’s parole if they discover they were given wrong information as part of the prisoner’s parole application.

When Does an Eligibility Date Apply?

If a defendant is sentenced for a serious violent offence[1] or a sexual offence.

a. A serious violent offence is when a person is sentenced for a violent offence for a period of 10 or more years.

b. A sexual offence is any sexual offence.

If a defendant is sentenced for a prison term longer than three years.

If the defendant was on parole, his parole was cancelled by the parole board, and the Court sentences him to a new term of imprisonment.

The defendant was on parole and he is sentenced to a term of imprisonment for an offence committed while on parole.

When does a Parole Release Date Apply?

If a parole eligibility date does not apply, then a parole release date will apply.

What is Parole?

Parole is when a person is serving a prison sentence, but doing so in the community. Under the mandatory conditions of parole include, a defendant must:

- report as directed to their supervising Office;

- carry out the lawful instructions issued by their supervising officer;

- give a test sample if required;

- notify of any change of address or employment details; and

- not to commit an offence.

The idea of parole is to supervise a defendant in the community while he serves the rest of his sentence. It also gives a defendant a greater opportunity to rehabilitate than he would have in prison.

If a person breaches any condition of his or her parole, the parole board has the power to cancel or suspend the parole, even if it was court-ordered parole.

What Happens if Parole Conditions are Breached?

According to the Corrective Services Act 2006, section 205, the parole board may, by written order—

- amend, suspend or cancel a parole order if the board reasonably believes the prisoner subject to the parole order—

has failed to comply with the parole order; or

poses a serious risk of harm to someone else; or

poses an unacceptable risk of committing an offence; or

is preparing to leave Queensland, other than under a written order granting the prisoner leave to travel interstate or overseas; or

-

amend, suspend or cancel a parole order, other than a court ordered parole order, if the board receives information that, had it been received before the parole order was made, would have resulted in the board making a different parole order or not making a parole order; or

-

amend or suspend a parole order if the prisoner subject to the parole order is charged with committing an offence; or

-

suspend or cancel a parole order if the board reasonably believes the prisoner subject to the parole order poses a risk of carrying out a terrorist act.

What Does the Parole Board Consider?

When deciding whether to release a person on parole, the parole board will consider multiple factors which include:

- the prisoner’s criminal history and pattern of offending;

- whether there are any circumstances likely to increase the risk the prisoner presents to the community;

- whether the prisoner has been convicted of a serious sexual offence or serious violent offence;

- any comments made by the Judge during the sentence hearing;

- any medical, psychological or psychiatric risk assessment reports relating to the prisoner – tendered at sentence or obtained while the prisoner has been in jail;

- the prisoner’s behaviour in prison;

- whether the prisoner has access to supports or services in the community;

- whether they have suitable accommodation upon release; and

- the prisoner’s progress and compliance in undertaking any recommended rehabilitation programs and interventions while in prison.

Conclusion

As can be seen, the law around parole and parole conditions is strict. While we at Clarity Law do everything possible to avoid our clients going to jail, sometimes it is inevitable. If it must happen, we have the knowledge and expertise to explain a parole order in detail, to ensure you have the best chance of completing your order.

[1] If a person is sentenced for a serious violent offence, he must serve the lesser of 80% of his term of imprisonment, or 15 years, before eligible for parole.

How Does the Court Set a Prison Sentence?

When imposing a prison sentence, a Queensland Court has two primary discretions. The first is to decide the length of the sentence, and the second is to set the release or eligibility date.

The basic structure of prison sentences

A prison sentence might be “six months imprisonment to be released on parole after having served two months”. This means that the prison sentence is six months, and the person is released from custody after two months. The remaining four months will be served on parole. Alternatively, the Court may order that the person serves four years to be eligible for parole after two years.

The two parts, then, are the length of the sentence, and then a parole release or parole eligibility date some time before the end of the sentence.

Setting length of the sentence

Sentencing in Queensland is a complex procedure in which the Court must consider many things, including:

-

The sentencing principles in the Penalties and Sentences Act;

-

Relevant case law (previously decided cases);

-

the maximum penalty of the offence;

-

the penalty submissions made by the prosecution;

-

the penalties submissions made by the defence;

-

the personal circumstances of the defendant;

-

the circumstances of the offence;

-

any victim impact statement;

-

the impact the offence had on an individual or the public generally;

-

any time in custody the defendant has already served before the sentence and;

-

the criminal history of the defendant.

As can be seen, there is a lot for the Court to consider.

The Queensland Supreme Court has said that sentencing is not a mathematical exercise. Judges and magistrates have a wide discretion in deciding how to impose a sentence. The primary approach is called an “instinctive synthesis”.

In practice, most judges and magistrates are likely to stay within the “range” of previously decided cases. “Range” means the upper and lower limits of the usual sentences imposed for a given offence. For example, a court is likely to impose a penalty of 18 months or more for drug trafficking. This is because most cases show sentences of 18 months imprisonment or more for that offence.

Setting the Release Date

It is rare for a defendant to serve the whole of the length of his prison sentence in custody. He will usually have the opportunity of parole.

As a general rule, a person who pleads ‘guilty’ to an offence will be released or eligible after serving approximately 1/3 of his or her sentence. A person who pleads ‘not guilty’ and loses the trial, will generally be released or eligible after 1/2 of the sentence.

The longer the sentence, the more difference this makes. The difference between 1/3 or 1/2 of six months is one month. The difference between 1/3 or 1/2 of five years is 10 months.

Release Date or Eligibility Date

When a court is deciding when to release a person on parole, it will impose either a “parole release date”, or a “parole eligibility date”.

A parole release date means the Court chooses the date of the defendant’s release. This can be anywhere from the first day of the sentence to the last day.

If the Court does not impose a release date, it will be an eligibility date. This means the Court will set the date for when the defendant is eligible to apply for parole. The defendant applies to the Parole Board for release. It is the Parole Board who decides his release date, as opposed to the Court. The parole board has up to 120 days after the prisoner’s parole application to decide whether to release the prisoner or not. The Parole Board may defer the decision to gather further information, in which case it has 150 days to decide. So, while the prisoner can apply for parole, it may not be granted for up to 150 days after his application.

What is the Most important factor for sentencing?

In our experience, every case is different, and no one case will necessarily be decided in the same way as another. However, the factors below will always be relevant.

The seriousness of the offence. This refers to how seriously the offence is considered at law. A person convicted of murder is always going to do jail time, regardless of every other factor, because of how serious the offence is. A person convicted of possessing a pipe to smoke drugs, however, is almost never going to be sentenced to jail. This is because the offence is not serious enough to warrant actual imprisonment.

Criminal history is a big factor. A person may commit an offence which is not especially serious, but because of his criminal history, it becomes serious. Breaching a domestic violence order is a common example of this. The breach itself may not be overly serious, but because the person has been sentenced for breaching domestic violence orders many times in the past, the Court may consider it has no other option but to impose actual imprisonment.

As outlined earlier, a court will consider previous cases which are similar to the one before it, and attempt to impose a sentence within those bounds. This is for the purpose of (among others) consistency. It would be unfair for one person to get a wildly different penalty from another person for the same offence.

Conclusion

This article is only an introduction to sentencing. We highly recommend if you are charged with any offence, let alone a serious one, that you engage experienced criminal law experts. Clarity Law can give you the individual advice and support you need to make the right move.

Why should I engage Clarity Law?

Quite frankly we care about getting the right outcome for our clients and helping them through one of the most difficult times in their lives.

In the face of a criminal law charge, selecting the right legal representation is paramount, and Clarity Law offers a unique blend of proficiency and empathy that sets us apart. Our firm is dedicated to providing clarity in the often complex world of criminal law. We believe that every client deserves a clear understanding of their rights and the legal process they're navigating.

Our experienced team of lawyers approaches each case with a commitment to open communication, ensuring you're informed every step of the way. With a proven track record of securing favourable outcomes, we have the expertise to navigate even the most intricate legal challenges.

At Clarity Law, we strive not only to be your staunch advocates but also to provide a supportive, understanding environment during this trying time. Choosing Clarity Law means choosing a team that will tirelessly work to protect your rights and pursue the best possible outcome for your case.

You can read more about our founder, Steven Brough’s, journey to starting Clarity Law by clicking here.

How do I get more information or engage you to act for me?

If you want to engage us or just need further information or advice then you can either;

-

Use our contact form and we will contact you by email or phone at a time that suits you

-

Call us on 1300 952 255 seven days a week, 7am to 7pm

-

Click here to select a time for us to have a free 15 minute telephone conference with you

-

Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

-

Send us a message on Facebook Messenger

-

Click the help button at the bottom right and leave us a message

We are a no pressure law firm, we are happy to provide free initial information to assist you. If you want to engage us then great, we will give you a fixed price for our services so you will know with certainty what we will cost. All the money goes into a trust account monitored by the Queensland Law Society and cannot be taken out without your permission.

If you don’t engage us that fine too, at least you will have more information on the charge and its consequences.

Other articles that may be of interest

What is a Barrister and Why Would I Need one?

The lawyers at Clarity Law are traditionally called solicitors. Clarity Law sometimes hires barristers to assist our clients.

What is the difference between a solicitor and a barrister, and why might you need one?

The Short History of Barristers

The profession of barristers, often referred to as advocates or counsel, boasts a rich and storied history dating back to ancient Rome. The origins of barristers can be traced to the Roman legal system, where specialized legal representatives known as "orators" were entrusted with presenting cases in the forum. This early incarnation laid the groundwork for the development of barristers in later legal systems.

The modern concept of barristers as distinct legal professionals emerged in England during the late Middle Ages. By the 16th century, the legal profession had become divided into two distinct groups: solicitors, who handled legal matters outside of court, and barristers, who were trained to argue cases before the courts.

In Australia, the tradition of barristers was inherited from England, and it was further shaped by the evolving legal landscape of the 19th and 20th centuries. The establishment of the Queensland Bar Association in the late 19th century marked a significant milestone in the formalization of the barrister profession in Queensland. Since then, barristers have played a vital role in the legal system, providing specialised advocacy, legal expertise, and representation in courts of law.

Why do Barristers wear Robes and a Wig?

Barristers wear robes and wigs as part of a traditional legal dress code that has its roots in English legal history. Here are the main reasons for this practice:

-

Historical Tradition: The tradition of wearing robes and wigs dates back several centuries to the 17th century in England. At that time, it was customary for members of the upper classes to wear formal attire when appearing in public, and this practice extended to the legal profession.

-

Symbol of Impartiality: The uniformity of robes and wigs is intended to create a sense of neutrality and impartiality. By concealing personal clothing and hairstyles, it emphasizes that the focus should be on the law and the proceedings, rather than the individual barrister.

-

Professionalism and Dignity: The attire is seen as a sign of professionalism and respect for the legal process. It sets a formal tone for court proceedings, underscoring the seriousness and importance of the matters being discussed.

-

Equality in Appearance: Robes and wigs serve to diminish distinctions in appearance between barristers. This is important in conveying the idea that all barristers are equal before the law, regardless of their personal background or status.

-

Historical Continuity: By adhering to these longstanding traditions, the legal profession pays homage to its historical roots and demonstrates continuity in the practice of law.

-

Identification of Role: The attire helps to distinguish barristers from other participants in the legal process, such as solicitors, judges, and court staff. This clear visual distinction aids in the smooth functioning of court proceedings.

-

Courtroom Decorum: The formality of the attire contributes to the overall decorum of the courtroom, reinforcing the gravity of the proceedings and creating a structured environment.

It's worth noting that while this tradition is still observed in some jurisdictions, it has evolved or been abolished in others. In Queensland the wearing of wigs and robes has been reduced with a greater emphasis on practical and comfortable courtroom attire. In most cases robes and wigs are only worn in the District or Supreme Court involviong criminal matters.

What’s the Difference Between a Barrister and a Solicitor?

The main difference between a barrister and solicitor is a barrister specialises in ‘higher’ court work, and he or she will tend to have less contact with a client, tending to have the client’s instructions conveyed to him through the solicitor. A barrister is a sole trader. Clients will generally not go directly to a barrister, but rather, solicitors approach the barrister to give him work. He is required to accept that brief and perform all work expected under the retainer.

Queensland has a court hierarchy. The highest court in the state is the Supreme Court, followed by the District Court, followed by the Magistrates Court. Barristers will tend to work in the Supreme Court and the District Court. Barristers will often be called upon to do anything more complicated than an adjournment in those courts, which can include trials, pre-trial applications, and sentences. Because barristers appear in those higher courts often, they will be well armed with knowledge of the different judges in those courts, as well as the most up-to-date case law relevant to the charges litigated in those courts.

A solicitor, on the other hand, will be the primary contact for the client. It will often be a solicitor who does the paperwork and who organises the preparation of documents such as character references, personal statements, and psychological reports. The solicitor will be the primary point of contact for the various agencies (prosecution, community corrections, the courts etc). Solicitors will tend to do most kinds of work in the Magistrates Court. More experienced solicitors may appear in the District Court and Supreme Court. Solicitors will be involved in the case from the start, whereas barristers only come into the picture later. In more complicated court proceedings, both the barrister and solicitor will appear in the court, but the barrister will speak to the judge or jury directly while the solicitor ‘instructs’ in a supporting role.

Why Would I Need a Barrister?

Mostly it comes down to expertise and experience. While we at Clarity Law have the skills and experience needed to do some things in the higher courts, we are just never going to have the same level of experience in those higher courts as a barrister. This is because the vast bulk of our work is concentrated in the Magistrates Court, whereas a barrister is almost always in the higher courts. Barristers are particularly helpful for complicated processes. For example, a trial by judge and jury is a complex and time-intensive undertaking. Barristers are trained and experienced in the rules of evidence, questioning witnesses, and preparing speeches for a jury. A solicitor will often lack this training and experience, or, if the solicitor has it, it will be basic compared to that of a barrister.

Another upside of retaining a barrister is there will be two heads working on a case instead of one.

How is a Barrister Chosen?

Speaking for myself, I have a pool of trusted barristers from which I recommend. The barrister I recommend to a client will depend on a few factors such as the barrister’s proven record with certain types of charges, the personality of the barrister and how well that might fit with the client, and how available a given barrister might be for the work I would need him to do. Choosing the right barrister will depend on the circumstances of the case and the needs and personality of the client. The client need not take my recommendation, but usually does.

Conclusion

Most of the time a barrister will come recommended for more complicated court procedures, especially those in the District and Supreme Courts. As always, whether a barrister is needed will be dependent on the specific circumstances of the client’s case. Suffice it to say, should a barrister be required, Clarity Law will choose a barrister we think best fits the requirements of the case and the client.

How do I get more information or engage you to act for me?

If you want to engage us or just need further information or advice then you can either;

-

Use our contact form and we will contact you by email or phone at a time that suits you

-

Call us on 1300 952 255 seven days a week, 7am to 7pm

-

Click here to select a time for us to have a free 15 minute telephone conference with you

-

Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

-

Send us a message on Facebook Messenger

-

Click the help button at the bottom right and leave us a message

We are a no pressure law firm, we are happy to provide free initial information to assist you. If you want to engage us then great, we will give you a fixed price for our services so you will know with certainty what we will cost. All the money goes into a trust account monitored by the Queensland Law Society and cannot be taken out without your permission.

If you don’t engage us that fine too, at least you will have more information on the charge and its consequences.